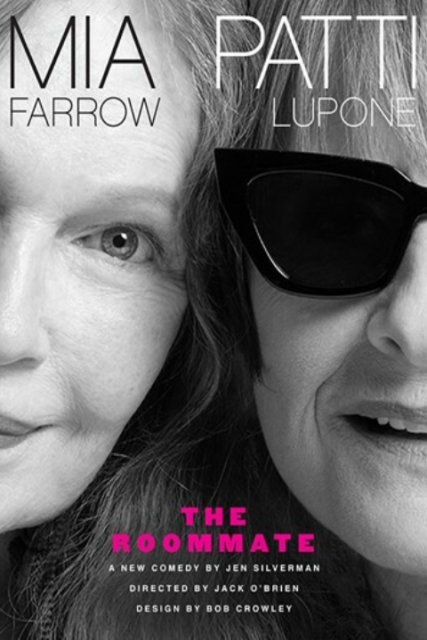

The Roommate, Jen Silverman’s slight two-character comedy at the Booth, begins in an unusual way. After the house lights have dimmed, the play’s stars Mia Farrow and Patti LuPone enter. Their names and a photo of them are projected on Bob Crowley’s sprawling farmhouse set. They acknowledge the audience’s applause, exit, and then re-enter in character to start the show. This tactic may just be a decision on director Jack O’Brien’s part to get the star factor out of the way and allow us to concentrate on the play at hand, but this blatant celebrity intro is an inadvertent acknowledge of the production’s raison d’être. We’re here to see two big names in rare circumstances—this is one of Farrow’s few stage appearances and an infrequent non-musical outing for LuPone, particularly after she very publicly renounced her Equity membership. Silverman’s play is a secondary consideration.

The Roommate itself is a flimsy effort derived from a familiar template. Two mismatched mature women, each seeking a new start after a crisis, are thrown together in a confined setting—in this case Crowley’s rambling, void-of-personal-details Iowa abode. One is retiring and shy (Farrow’s Sharon), the other eccentric, risk-taking, somewhat mysterious (LuPone’s Robyn). LuPone unbelievably has driven all the way from NYC, the Bronx to be specific, to share Farrow’s Midwestern home. Presumably they met through an Internet ad. Sharon has “retired” from her marriage. The cryptic Robyn appears to be on the run from an unspecified shady past. There is the inevitable pot-smoking scene, wherein weed virgin Sharon lets her hair down.

The formula is tried but not so true with the ladies, after some forced comedy about eating habits and estrangement from their respective grown children, bonding to become fast friends. John Ford Noonan’s A Coupla White Chicks Sitting Around Talking applied this trope with more skill as did David Auburn in his much stronger Summer, 1976 two seasons ago.

Predictably, the mousy Sharon breaks out of her conventional shell and finds Robyn’s unconventional habits attractive. Robyn is gay, vegan, grows marijuana, and refuses to conform to sexual or social labels. Without revealing any spoilers, we eventually learn the true nature of Robyn’s shadowy background and it further entices the curious, thrill-hungry Sharon. As expected, the conflict arises when Sharon goes too far into Robyn’s sketchy domain and Robyn backs off.

One particular scene exemplifies the play’s unrealized potential for insight and commentary. The formerly staid Sharon, now deeply into Robyn’s sphere of borderline nefarious activities, proudly displays a new AR-15 rifle she picked up with no hassles at the local Walmart. Robyn is freaked out and demands she take it back. Not only does Silverman break Chekhov’s Gun Rule—never display a firearm unless someone on stage is going to use it—but she fails to develop the issues raised by Sharon’s purchase. Sharon speaks of the seductiveness of owning a powerful weapon while Robyn, used to dealing with danger, sees only tragedy. The magnetic pull of firearms and the horrific rift they cause in our current political scene are barely touched on. Sharon puts the gun away and promises to return it. The two late-in-life characters, their roles in the larger society and how it treats them, are similarly shortchanged. Crowley’s skeletal set also has little evidence of either woman’s life or interests. But his character-suggesting costumes offer clues as to their backstory as does Natasha Katz’s evocative lighting and David Yazbek’s warm, rich original music.

Despite the slimness of Silverman’s script, her stars, directed with economy and precision by O’Brien, do their best to beef up their scrawny roles. Farrow delightfully conveys Sharon’s slow blossoming as she invents fanciful scenarios to flesh out her fantasies. Her relish at creating a life beyond the vast midwestern spaces is infectious. LuPone has less to work with since Robyn reveals less of her inner life and motivations for her not-quite-legal background. But she endows her character with a rich subtext, hinting at her past through sly smiles and a far-away mistiness in her eyes. Her look of regret and fear when Farrow hovers around the edges of peril suggests an untold narrative informing her reserve. There are hints of depth in LuPone’s Robyn. Too bad Silverman fails to deliver them.