The prospect of the great ballet dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov and Jessica Hecht, one of our most versatile and expressive actresses, in a new adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s classic The Cherry Orchard was an exciting and irresistible prospect. But The Orchard, director-conceiver Igor Golyak’s sci-fi deconstruction of this beloved portrait of a Russian landowning family displaced by overwhelming change, has so much going on that the passions, humor, and sorrow of the original are almost obliterated.

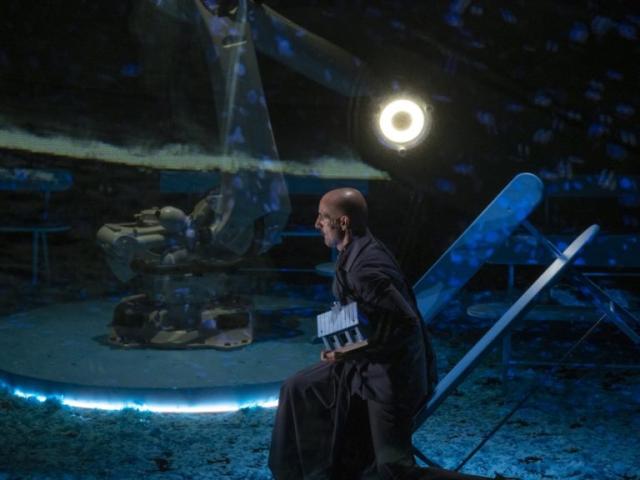

My first warning of trouble came when entering the Baryshnikov Arts Center and being confronted with what appeared to be either a gigantic mechanical sculpture or a piece of misplaced medical equipment. This ultramodern item stuck out like a sore thumb amid Anna Fedorova’s abstract blue-toned set which was littered with blue confetti (cherry blossoms, perhaps, but the wrong color). The huge object turns out to be a robotic arm with a camera at one end which projects images of the action on a scrim at the edge of the stage and onto the Internet for those viewing the play in a digital version (more on that later).

The arm moves, stands in for a bookcase and a tree, manipulates props, and becomes a sort of character, as does a cute robot dog. In addition, there’s an online auction among those at home watching the play, taking place simultaneously during the auction for the cherry orchard itself. Translations from various languages including Russian, French, and ASL periodically and inconsistently appear on the scrim as do random stage directions. These digital and mechanical devices don’t really add much to the story or effectively support Golyak’s interpretation but distract from Chekhov’s compassionate depiction of the flawed family, their friends and servants. (For some reason, the comic servants Yasha, Dunyasha, and Yepikhodov and the lovably buffoonish neighbor Simeonov-Pischik have been eliminated. Their humorous relief is much missed.)

If these futuristic touches served to emphasize the Ranevskys’ disconnection with an increasingly unfamiliar society they would make sense, but they just seem to be inserted just to allow multiple camera angles and blown-up images. It’s a pity because the solid international cast does convey loads of subtext. Too bad Golyak’s gimmicks obscure their fine work.

Baryshnikov is illuminatingly tender as the ancient servant Firs, usually a supporting role, but beefed up here. The magnificent dancer gives specific physical life to this remnant of a bygone era in evocative dance movement, unfortunately difficult to discern because of Golyak’s busy staging and Yuki Nakase Link’s dim lighting. Oana Botez’s dark-hued, monochromatic costumes don’t help lightening things up.

Jessica Hecht captures the dithery charm and intense passion of Ravenskaya, oblivious to her dwindling chances to save her home and focused only on past regrets and present amours. The scene where the former peasant Lopakhin, who has taken possession of the estate, fails to propose to Raneskaya’s lonely daughter Varya, is particularly heartbreaking and beautifully played by Nael Nacer and Elise Kibler. Kimber is especially moving as her giddiness at the possibility of marriage fades into the sad realization that Lopakhin will never pop the question. There is also detailed limning in the form of Mark Nelson’s frivolous Gaev, Darya Denisova’s boisterous governess Charlotta Ivanovna, Juliett Brett’s earnest Anya, and John McGinty’s intense radical student Trofimov (even though the deaf actor’s sign language is not always interpreted for us, his intentions are clear).

The only sequence where Golyak’s reimagining completely works is when a passer-by interrupts a family picnic. In Chekhov’s original, a sound like a wire snapping (representing a breaking of the old order) precedes the entrance of a vagrant (the underclass) who briefly alarms the sheltered aristocrats and foreshadows their destruction. Here, the sound is an explosion and the passer-by is a brutish thug (a menacing Ilia Volok), speaking in untranslated Russian, who physically harasses the frightened party and sexually assaults the terrified Varya. The explosion and the intruder can represent the Bolshevik Revolution, the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl, and/or the current Russian invasion of Ukraine (Golyak’s home country). The muddled production suddenly becomes horrifying real.

The virtual version of the play is not that much different from the live experience. Before joining the production in real time, Internet viewers are given a tour of the theater, opening into various virtual spaces where Baryshnikov plays the playwright and he and Hecht read letters and diary entries. It’s an enchanting but short addendum. We then join the play and have the option of seeing it from the robot camera’s POV. When I watched the digital edition two nights after seeing the live staging, my laptop’s screen kept freezing and I had to hit the refresh button several times. Just as with the actual production presented behind a scrim and cluttered with robots, too much technology interfered with Chekhov’s timeless vision.