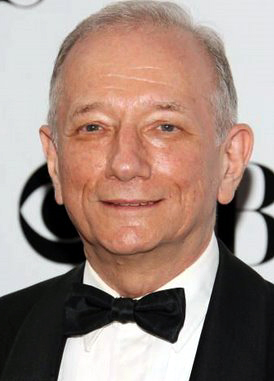

If you're reading this article, chances are you're well aware that Jonathan Tunick is the orchestrator of several all-time-great Broadway shows, including the lion's share of Stephen Sondheim's masterpieces as well as A Chorus Line and Promises, Promises.

What you may not know is that Tunick is an "EGOT," one of precious few artists who've been honored with an Emmy, a Grammy, an Oscar, and a Tony (1977 Academy Award for Best Music, Original Song Score and its Adaptation or Best Adaptation Score, A Little Night Music; 1982 Emmy for Outstanding Achievement in Music Direction, "Night of 100 Stars"; 1988 Grammy for Best Instrumental Arrangement Accompanying Vocals, "No One Is Alone" as sung by Cleo Laine; and a 1997 Tony for Best Orchestrations, Titanic). In anticipation of the Broadway opening of the Kennedy Center revival of Sondheim's Follies, I spoke with Jonathan about the art of the orchestrator.

MICHAEL PORTANTIERE: When you orchestrated Follies for the original production in 1971, did you approach the pastiche numbers differently from the other songs?

JONATHAN TUNICK: Yes. The score of Follies is built on three different levels. There's the actual score of the show, the character numbers. Then there are what we call the pastiche numbers, in which some of the characters do their turns, singing the songs they would have done in the actual Follies. Then there's the end of the show, the "Loveland" sequence, which takes the Follies style into overdrive. The "Loveland" songs are really a combination of the pastiche numbers and the character numbers; they're meant to take you into this weird, surrealistic fantasy. It's hard to describe, because I don't think anything like that had ever been done before.

MP: And probably not since! When you were orchestrating the songs that evoke a previous era, did you study the work of previous composers and orchestrators and try to emulate it?

TUNICK: Oh yes, very much so. In fact, I've given some of the orchestrations pet names. For instance, I call "Ah, Paris!" my Robert Russell Bennett number. "I'm Still Here" is your Harold Arlen ballad from the '40s. And I always think of "Rain on the Roof" as a movie number -- not from an M-G-M musical, but maybe a 20th Century-Fox musical.

MP: When you orchestrate a Sondheim score, is the basic process that you and he discuss it beforehand, then you go off and do your work, then you present it to him and he makes comments and suggests changes?

TUNICK: That pretty much describes it. But I'm pleased to say that he gives me a free hand for the most part, and he only occasionally asks for a change.

MP: You've been a vocal critic of the ever-decreasing size of orchestras on Broadway, so I imagine you're very gratified by the employment of a full orchestra for this revival of Follies.

TUNICK: Oh, yes. It reminds us of what we're losing. I don't think there's any better example than Follies of what an orchestra can do for a musical if given a chance.

MP: Would you agree that the over-amplification of musicals has contributed to the shrinkage in orchestra size?

TUNICK: That's a hard one to answer. To me, it just makes it louder. That's what amplification is, by definition. It doesn't make it better.

MP: Promises, Promises was the first Broadway show in which the orchestra was amplified. Do you think it set a dangerous precedent?

TUNICK: That show was written by a composer who had a recognizable instrumental sound. Part of that sound was the sound of a studio, so it was necessary to try to evoke that effect in the theater. But Promises, Promises was a special case, because Burt Bacharach never wrote another musical. I wish he had.

MP: Would you say it's a good or bad thing in general that all Broadway orchestras are amplified nowadays?

TUNICK: Oh, let's not get into that.

MP: Fair enough. Tell me, how do you decide which instruments to use when it's not a traditional orchestra -- for example, Merrily We Roll Along. I've always wondered why that show has no strings other than a bass and a cello.

TUNICK: I think there are two reasons. One is that the show was planned to have a somewhat smaller orchestra than usual. When you're talking about violins, you're talking about a fairly large number of musicians, so a quick way to get your orchestra down from 25 players to 19 is not to use any violins. Also, Merrily We Roll Along was presented to me as a musical full of wit and humor and youthful abandon. That suggested a sort of satirical orchestra, and it also suggested downplaying the strings.

MP: As for A Chorus Line, do those orchestrations have no strings simply because the show started at the Public Theater with a smaller orchestra?

TUNICK: Yes. We had 16 players downtown. Then we moved uptown, and to me it was a no-brainer: "Let's write in 10 strings. The ballads will sound wonderful, and the underscoring will have some body to it." But Michael Bennett didn't want to do that. I think it was superstition on his part; he didn't want to change anything from downtown.

MP: According to a website I found, you're one of only 10 people who've won an Oscar, a Tony, an Emmy, and a Grammy.

TUNICK: Apparently, it's true, to one degree or another. The number changes depending on who [sic] you speak to. I've heard every number from five through eight, but this is the first time I've heard 10.

MP: Whatever the exact number, it's very impressive, especially considering that there haven't always been Tony Awards for orchestrations. And how wonderful but ironic that you won your Oscar for A Little Night Music, given that the film as a whole was so poorly received.

TUNICK: Well, I think they wanted to give an Oscar to Steve [Sondheim], but he wasn't eligible because [most of] the score had been written for the theater, not for the screen. So I think I got that award by default.

MP: Is there anything else you'd like to say about Follies before I let you go?

TUNICK: Follies is an extraordinary musical steeped in theatrical history and magic. To see it again in such a good production is really a thrill.

[END]