This year’s conference of the American Theater Critics Association overlapped and interacted with the 29th annual Tennessee Williams New Orleans Literary Festival. David Kaplan, curator of the ten-year-old Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival, was on hand to direct a co production of the Hotel Plays.

Thomas Lanier "Tennessee" Williams III (March 26, 1911 – February 25, 1983) declared that "Life is cannibalistic." This metaphor was vividly conveyed in a festival production of Suddenly Last Summer performed by Southern Rep. Mrs. Violet Venable (Brenda Currin), a hysteric modeled on his mother Edwina, is determined to have Catherine Holly (Beth Bartley) lobotomized. Declaring her mentally incompetent will nullify an accurate account of how her son Sebastian was devoured by a horde of ravenous young men he had molested. In a confluence of fact and fiction, Edwina orchestrated the lobotomy of her daughter Rose.

In a discussion of his recently published biography, “Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh,” the former New Yorker critic, John Lahr, suggested that the daily writing sessions of Williams were a means of responding to his mother who talked incessantly but never listened. His cruel, abusive, alcoholic father (the inspiration for Big Daddy in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof) ridiculed him as the sissy his mother had tormented him into becoming. These family-inflicted traumas encouraged him to retreat into writing as a means of livelihood and survival.

Looking around and noting the dimensions of the hotel conference room Lahr suggested that, literally, stacked up, the papers of Williams would fill it. During the commitment to writing the biography Lahr revealed that he hadn't read everything. In fact it is impossible.

The last Williams hit, Night of the Iguana, based on the 1948 story, was produced on Broadway in 1961. While continuing to work for the next 22 years, Williams was largely viewed as a washed up lush/addict. While much of the late work is described as muddled and mediocre, including one-act plays, short stories, letters and poetry, Lahr has diligently panned it for nuggets.

Understanding of the vast material of the late period was hindered by the executor of the estate, a Williams confidante, Maria St. Just. She denied access to scholars and is said to have taken a razor blade to documents that contained unflattering references to herself. Her only interest was generating some $300,000 a year to keep Rose in the style she had become accustomed to. Until the death of St. Just, and the easing of access, the reputation of Williams languished. When St. Just died, Lahr published a scorching profile of her in the New Yorker. Scoffing at the notion of “newly discovered” plays, Lahr said that they were sitting in boxes in the archives.

While Williams was alive, Lahr had been approached about writing a biography. Nothing came of that plan until Lyle Leverich, a former theatre producer who had never written a book, became the "official" biographer. St. Just held up that publication, which covered the early years through 1944. The Glass Menagerie premiered that year with 24 curtain calls.

In 1994, Lahr started his project and initiated dialogues with Leverich. His biography, "Tom: The Unknown Tennessee Williams," was published in 1995. When Leverich passed away, Lahr inherited boxes of archival material. He also had access to the essential papers of Elia Kazan who had a major role in shaping the plays into revenue-producing hits. There were intense arguments about cuts and revisions and even alternative versions, but in the end, Williams was seduced by the money.

When the end came, there were several days of silence. Williams was spent. He had cannibalized himself. There was nothing left to give. It is such a morbid and pathetic image of one of the greatest playwrights of the 20th century.

Some 40 books have been published on Williams. While stating that his book has been well reviewed, Lahr dismisses the others. He said most theatrical biographies are more about typing than writing. Mostly they fail to analyze the plays. As a distinguished critic, he is particularly interested in how, via Elia Kazan’s stewardship, the plays took shape on stage.

Admittedly, some of the reviews for “Tom” I read were less flattering than Lahr conveyed. One stated that the prose of Lahr was no match for that of Williams. But wouldn't you hope for that to be the case? It's an interesting question of whether the best critics can match those they write about. Consider Boswell on Dr. Johnson, for example.

As Lahr suggests, we must see the plays as a sweeping progression of Williams’s horrific family and brutal life experiences. They are in that regard one long story with characters created from his inner demons and tormented psyche. But Lahr insists that the biography is not a cheap attempt at psychoanalysis. He only conveys the facts and lets the reader draw conclusions. "There is not one psychological term in the book" stated Lahr who is allegedly undergoing psychoanalysis. Lahr also notes that in Williams’s final play, A House not Meant to Stand, the dramatist was bidding farewell to his repertory company of characters.

While Williams enjoyed his celebrity, it left him with few peers and no friends. At the end of days spent writing fueled by booze and amphetamine, he was in no shape for casual conversation. In the French Quarter, he staggered across the street to dine at Marti's. After one of the ATCA sessions, a group of us were led to see Williams’s home and to enjoy a late supper in the restaurant. We saw his favorite corner banquette, but the kitchen had just closed at 10:30 PM. Astrid and I returned for a nostalgic dinner during our last night in The Big Easy.

There were tricks, twinks, rough trade and lovers, but other than sex, one wonders what they could actually share with a shattered monument. One senses that Williams was never really whole other than when writing so compulsively.

It makes me think of a fairy tale with the task of spinning straw into gold. Yes, there was that brilliant glitter, some of the finest of his era, but scholars and critics like the often cruel and clever Robert Brustein remind us that much of it remained just straw. The writing is of interest only because of its source.

And yet, fans or vultures, as in Suddenly Last Summer we continue to tear at his flesh. The cruelest and most avid among us, alas critics, pluck out his eyes while feasting on heart and soul. If Williams has been adored and devoured, then we are the cannibals. But what tasty flesh when taken with a bit of gris gris and voodoo. It is little wonder that Williams loved the decadence of New Orleans with its exotic flavors and dangerous games.

Given the ravishing morbidity, there was passion and pleasure in this séance conjuring the ghost of an artist who endured the life of the living dead in a private hell of family and memory. How wonderful of a company of artists to give us this exotic and evocative experience.

There was the exquisite performance of The Hotel Plays including Last of My Solid Gold Watches, Lord Byron's Love Letter, Mister Paradise and Lady of Larkspur Lotion. They were performed in rooms in the historic Hermann-Grima House. An audience of about 25 crammed in as the actors were inches away from us. With no special lighting or props, there was a raw visceral quality of being so close that we were absorbed into the action. They were vignettes, fragments and poems that defy critical deconstruction and a search for meaning. Though the one-acts were quite wonderful, we were told that they were better on other occasions. A rainy day prevented parts of them from being staged outdoors.

The traditional jazz band which played as we exited was to have been used differently and more effectively. But for me, no matter, it was a deliciously decadent and life-changing experience. The elderly character actor Cristine McMurdo-Wallis was simply divine. We enjoyed her immensely during an evening of “Blue Devils and Better Angels,” a Tennessee Williams Tribute Reading at the Ursulines' convent in the French Quarter. (We never entered the oldest structures in New Orleans as the event was staged under a tent. It was set up for a wedding including chandeliers.)

Because a scheduled participant was unable to attend, McMurdo-Wallis provided the first two readings. Considering that there were no rehearsals, she provided subtle and polished, evocative readings. One was from the letter describing a two-week love affair and his sexual awakening. Williams was so oppressed by his mother and riddled with sexual doubt that he didn't even masturbate until he was in his mid twenties. The actors Keir Dullea and Mia Dillon performed from a two-hander. A reading by John Waters was suitably quirky. There were also selections by advice columnist Amy Dickinson and British mystery writer Rebecca Chance.

It seemed a bit odd when playwright John Patrick Shanley barely referenced Williams as he read from a play, Prodigal Son, which is headed to Broadway next season. Even more askew, he mis-buttoned his leather jacket. He conveyed an uncouth Irish kid from the hood which was precisely one of the two characters he was reading. It was distracting that he repeated the name of the characters. It seems that could have been conveyed by different inflections of the kid and the head master of a boarding school.

On Saturday night, we enjoyed a staged reading of a brief one-act, I Never Get Dressed Till After Dark on Sundays by the itinerant NOLA Project.

Today, through Amazon Prime, I ordered the Lahr biography. It's some 700 pages, and I'm a slow reader. Astrid also wants to read it. She is suggesting that she can have it in the morning, and I can have it on the afternoon. A better idea is to have her read it first. She's pretty quick. Hopefully we will both have finished in time for the Williams Festival in P'Town come September.

By then I will be starved for more of Williams's steak tartare.

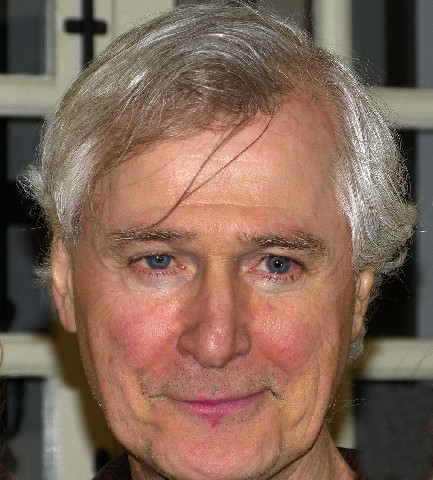

pictured: John Lahr, John Patrick Shanley, NOLA Project, the band.